Sokrates

| Thời đại | Triết học cổ |

|---|---|

| Lĩnh vực | Triết học phương Tây |

Sokrates hay Socrates (tiếng Hy Lạp: Σωκράτης Sōkrátēs) là một triết gia Hy Lạp cổ đại, người được mệnh danh là bậc thầy về truy vấn. Về năm sinh của ông hiện vẫn chưa có sự thống nhất giữa năm 469 hay 470. (469–399 TCN), (470–399 TCN). Ông sinh ra tại thành phố Athens, thuộc Hy lạp, và đã sống vào một giai đoạn thường được gọi là hoàng kim của thành phố này. Thời trẻ, ông nghiên cứu các loại triết học thịnh hành lúc bấy giờ của các "triết học gia trước Sokrates", đó là nền triết học nỗ lực tìm hiểu vũ trụ thiên nhiên chung quanh chúng ta. Tên ông được phiên âm ra tiếng Việt thành Xô-crát.

Sokrates được coi là nhà hiền triết, một công dân mẫu mực của thành Athena, Hy Lạp cổ đại. Ông là nhà tư tưởng nằm giữa giai đoạn bóng tối và giai đoạn ánh sáng của nền triết học Hy Lạp cổ đại. Sokrates còn được coi là người đặt nền móng cho thuật hùng biện dựa trên hệ thống những câu hỏi đối thoại. Ông có tư tưởng tiến bộ, nổi tiếng về đức hạnh với quan điểm: “Hãy tự biết lấy chính mình”, “Tôi chỉ biết mỗi một điều duy nhất là tôi không biết gì cả”. Ông bị chính quyền khi đó kết tội làm bại hoại tư tưởng của thanh niên do không thừa nhận hệ thống các vị thần cũ được thành Athena thừa nhận và bảo hộ và truyền bá các vị thần mới. Vì thế ông bị tuyên phạt tự tử bằng thuốc độc, mặc dù vậy ông vẫn có thể thoát khỏi án tử hình này nếu như ông công nhận những cáo trạng và sai lầm của mình, hoặc là rời bỏ Athena. Nhưng với quan điểm "Thà rằng chịu lỗi, hơn là lại gây ra tội lỗi.", ông kiên quyết ở lại, đối diện với cái chết 1 cách hiên ngang. Theo ông sự thật còn quan trọng hơn với cả sự sống.

Sinh thời ông không mở trường dạy học, mà thường coi mình là có sứ mệnh của thần linh, nên phải đi dạy bảo mọi người và không làm nghề nào khác. Sokrates thường nói chuyện với mọi người tại các nơi công cộng, tại các agora và không lấy tiền, nên ông chấp nhận sống một cuộc sống nghèo. Học trò xuất sắc của ông là đại hiền triết Platon từng theo học trong 8 năm ròng.

Mục lục

[ẩn]Tiểu sử[sửa]

"Vấn đề Sokrates"[sửa]

Phác hoạ một hình ảnh chính xác về tiểu sử của Sokrates và quan điểm triết học của ông là một nhiệm vụ vô cùng gian nan.

Sokrates không viết các tác phẩm triết học. Hiểu biết của chúng ta về ông, cuộc đời và sự nghiệp của ông dựa trên ghi chép của các học trò và người cùng thời. Đầu tiên trong số đó là Plato; tuy nhiên, tác phẩm của Xenophon, Aristotle, và Aristophanes cũng cung cấp những hiểu biết sâu sắc[1]. Tìm kiếm một hình ảnh Socrates “thật sự” là một điều rất khó khăn bởi những tác phẩm đó thường mang tính triết lý hay là kịch hơn là sự thật lịch sử. Ngoài ra từ Thucydides (người không đề cập đến Socrates hay các triết gia nói chung), thật sự không có một tiểu sử thực thụ của những người cùng thời với Plato. Kết quả tất yếu của điều đó là những nguồn đó đã không mâu thuẫn với sự chính xác lịch sử. Các nhà sử học trước kia phải đối mặt với việc làm hòa hợp rất nhiều tài liệu để tạo nên sự miêu tả chính xác về cuộc đời và công việc. Kết quả của những nỗ lực như thế là sự tất yếu mang tính hiện thực, là sự thống nhất đơn thuần.

Về tổng quan, Plato được xem như là nguồn thông tin chắc chắn về cuộc đời và tác phẩm của Socrates [2]. Tuy nhiên, điều đó cũng được làm sáng tỏ trong các tài liệu và các tác phẩm lịch sử tằng Socrates không đơn giản chỉ là nhân vật, hay phát minh của Plato. Sự chứng nhận của Xenophon và Aristole, theo như một số tác phẩm của Aristophane trong The Clouds, có thể hữu dụng trong việc liên kết nhận thức về một Socrates bằng xương bằng thịt bên cạnh các tác phẩm của Plato

Cuộc đời[sửa]

Chi tiết về Socrates có nguồn gốc từ ba tác phẩm của những người cùng thời: the dialogues của Plato và Xenophon (đều là người say mê Socrates), và các vở kịch của Aristophanes. Ông cũng được miêu tả bởi một vài học giả, kể cả Eric Havelock và Walter Ong, quán quân của việc kể truyền miệng, đứng sừng sững vào buổi bình minh của văn viết chống lại sự truyền bá bừa bãi.

Vở kịch The Clouds của Aristophane miêu tả Socrates như là một chú hề dạy dỗ học trò của mình cách thức lừa bịp để thoát nợ. Dĩ nhiên hầu hết tác phẩm của Aristophane đều mang tính chất châm biếm. Vì lẽ đó nó được cho là sự thành công trong việc xây dựng nhân vật tiểu thuyết hơn là miêu tả chân thực.

Theo Plato, cha của Socrates là Sophroniscus và mẹ là Phaenarete, một bà đỡ. Dù được miêu tả như một mẫu người thiếu sức hấp dẫn bề ngoài và có vóc người nhỏ bé nhưng Socrates vẫn cưới Xanthippe, một cô gái trẻ hơn ông ta rất nhiều. Cô ấy sinh cho ông ba đứa con trai Lamprocles, Sophroniscus và Menexenus. Bạn của ông là Crito của Alopece chỉ trích ông về việc bỏ rơi những đứa con trai của ông khi ông từ chối việc cố gắng trốn thoát khỏi việc thi hành án tử hình.

Không rõ Socrates kiếm sống bằng cách nào. Các văn bản cổ dường như chỉ ra rằng Socrates không làm việc. Trong Symposium của Xenophon, Socrates đã nói rằng ông nguyện hiến thân mình cho những những gì ông coi là nghệ thuật hay công việc quan trọng nhất: những cuộc tranh luận về triết học. Trong The Clouds Aristophanes miêu tả Socrates sẵn sàng chấp nhận trả công cho Chaerephon vì việc điều hành một trường hùng biện, trong khi ở Apology và Symposium của Plato và sổ sách kể toán của Xenophon, Socrates dứt khoát từ chối việc chỉ trả cho giảng viên. Để chính xác hơn, trong Apology Socrates đã viện dẫn rằng cảnh nghèo nàn của ông ấy là chứng cớ cho việc ông ấy không phải là một giáo viên. Theo Timon của Phlius và các nguồn sau này, Socrates đảm nhận việc trông coi xưởng đá từ người cha. Có một lời truyền tụng cổ xưa, chưa được kiểm chứng bởi sự các học giả, rằng Socrates đã tạo nên bức tượng Three Grace ở gần Acropolis, tồn tại cho đến tận thế kỉ thứ 2 sau Công nguyên.

Một số đoạn đối thoại của Plato quy cho việc Socrates phục vụ trong quân đội. Socrates nói ông phục vụ trong quân đội Athen trong suốt ba chiến dịch: tại Potidaea, Amphipolis, và Delium. Trong Symposium Alcibiades mô tả sự dũng cảm của Socrates trong trận Polidaea và Delium, kể lại chi tiết việc Socrates cứu mạng ông ta như thế nào tại cuộc chiến trước (219e – 221b). Sự phục vụ bất thường của Socrates ở Delium cũng được đề cập đến trong tác phẩm Laches với vị tướng cùng tên với đoạn đối thoại (181b). Trong Apology, Socrates so sánh sự phục vụ trong quân đội với việc ông bị rắc rối ở phòng xử án, và nói với tất cả bồi thẩm đoàn nghĩ rằng việc ông nên từ bỏ triết học cũng phải nghĩ rằng những người lính nên chạy trốn mỗi khi họ thấy họ có thể bị giết trong chiến trận.

Cuộc xử án và cái chết[sửa]

Cái chết của Socrates (La Mort de Socrate, 1787), họa phẩm của Jacques-Louis David, hiện được trưng bày ở Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mặc dù luôn thể hiện sự trung thành đến chết với thành bang, song việc Socrates theo đuổi đến cùng lẽ phải và đức hạnh của ông đã mâu thuẫn với chiều hướng chính trị và xã hội đương thời của Athena. Ông ca ngợi Sparta, chê bai Athena, trực tiếp và gián tiếp trong nhiều cuộc đối thoại. Nhưng có lẽ hầu hết các sử liệu xác thực đều cho thấy sự đối lập của Socrates với thành bang là ở quan điểm chỉ trích xã hội và luân lý của ông. Thích bảo vệ sự nguyên trạng hơn là chấp nhận phát triển sự phi đạo đức. Trong lĩnh vực của mình Socrates cố gắng phá vỡ quan niệm lâu đời “chân lý thuộc về kẻ mạnh” rất thông dụng ở Hy Lạp lúc bấy giờ. Plato cho Socrate là “ruồi trâu” của nhà nước (như một con ruồi châm chích con trâu, Socrates châm chọc Athen. Quá đà hơn ông chọc giận các nhà quản lý với ý kiến đòi xem xét các phán quyết toà án và các quyết định. Cố gắng của ông để tăng cường ý thức của tòa án Athena có lẽ là nguồn cơn cho việc hành hình ông.

- Ông tin rằng sự trốn chạy là biểu hiện của sự sợ hãi cái chết, bở ông tin không triết gia nào làm thế.

- Nếu ông trốn khỏi Athena, sự dạy dỗ của ông không thể ổn thỏa hơn ở bất cứ nước nào khác như ông đã từng truy vấn mọi người ông gặp và không phải chịu trách nhiệm về sự không vừa ý của họ.

- Bằng sự chấp thuận sống trong khuôn khổ luật của thành bang, ông hoàn toàn khuất phục chính bản thân ông để có thể bị tố cáo như tội phạm bởi các công dân khác và bị tòa án của nó phán là có tội. Mặt khác có thể ông bị kết tội vì phá vỡ sự “liên hệ cộng đồng” với Nhà nước, và gây tổn hại đến Nhà nước, một sự trái ngược so với nguyên lý của Socrates.

Cái chết của Socrates được diễn tả ở phần cuối của cuốn Phaedo của Plato. Socrates bác bỏ lời cầu xin của Crito để cố gắng thử trốn khỏi tù. Sau khi uống độc dược, ông vẫn được dẫn đi dạo cho đến khi bước chân ông trở nên nặng nề. Sau khi ông gục xuống, người quản lý độc dược véo thử vào chân ông. Socrates không còn cảm giác ở chân nữa. Sự tê liệt dần dần lan khắp cơ thể ông cho đến khi nó chạy vào tim ông. Không lâu trước khi ông chết, Socrates trăng trối với Crito “Crito, chúng ta nợ một con gà trống với Asclepius. Làm ơn đừng quên trả món nợ đó”. Asclepius là thần chữa bệnh của người Hy Lạp, và những lời cuối cùng của Socrates nghĩa là cái chết là cách chữa bệnh và sự tự do là việc tâm hồn thoát ra khỏi thể xác. Nhà triết học La Mã Secena đã thử bắt chước cái chết của Socrates khi bị ép tự tử bởi Hoàng đế Nero.

Triết học[sửa]

Phương pháp Socrates[sửa]

Phương pháp Socrates có thể được diễn tả như sau; một loạt câu hỏi được đặt ra để giúp một người hay một nhóm người xác định được niềm tin cơ bản và giới hạn của kiến thức họ. Phương pháp Socrates là phương pháp loại bỏ các giả thuyết, theo đó người ta tìm ra các giả thuyết tốt hơn bằng cách từng bước xác định và loại bỏ các giả thuyết dẫn tới mâu thuẫn. Nó được thiết kế để người ta buộc phải xem xét lại các niềm tin của chính mình và tính đúng đắn của các niềm tin đó. Thực tế, Socrates từng nói, "Tôi biết anh sẽ không tin tôi, nhưng hình thức cao nhất của tinh túy con người là tự hỏi và hỏi người khác” [3]

Niềm tin triết học[sửa]

Người ta khó phân biệt giữa các niềm tin triết học của Socrates và của Plato. Có rất ít các căn cứ cụ thể cho việc tách biệt quan điểm của hai ông. Các lý thuyết dài biểu đạt trong đa số các đoạn hội thoại là của Plato, và một số học giả cho rằng Plato đã tiếp nhận phong cách Socrates đến mức lảm cho nhân vật văn học và chính nhà triết học trở nên không thể phân biệt được. Một số khác phản đối rằng ông cũng có những học thuyết và niềm tin riêng. Nhưng do khó khăn trong việc tách biệt Socrates ra khỏi Plato và khó khăn của việc diễn giải ngay cả những tác phẩm kịch liên quan đến Socrates, nên đã có rất nhiều tranh cãi xung quanh việc Plato đã có những học thuyết và niềm tin riêng nào. Vấn đề này còn phức tạp hơn nữa bởi thực tế rằng nhân vật Socrates trong lịch sử có vẻ như nổi tiếng là người chỉ hỏi mà không trả lời với lý do mà ông đưa ra là: mình không đủ kiến thức về chủ đề mà ông hỏi người khác.[4]Nếu có một nhận xét tổng quát về niềm tin triết học của Socrates, thì có thể nói rằng về mặt đạo đức, tri thức, và chính trị, ông đi ngược lại những nguời đồng hương Athena. Khi bị xử vì tội dị giáo và làm lũng đoạn tâm thức của giới trẻ Athena, ông dùng phương pháp phản bác bằng lôgic của mình để chứng minh cho bồi thẩm đoàn rằng giá trị đạo đức của họ đã lạc đường. Ông nói với họ rằng chúng liên quan đến gia đình, nghề nghiệp và trách nhiệm chính trị của họ trong khi đáng ra họ cần lo lắng về "hạnh phúc của tâm hồn họ". Niềm tin của Socrates về sự bất tử của linh hồn và sự tin tưởng chắc chắn rằng thần linh đã chọn ông làm một phái viên có vẻ như đã làm những người khác tức giận, nếu không phải là buồn cười hay ít ra là khó chịu. Socrates còn chất vấn học thuyết của các học giả đương thời rằng người ta có thể trở nên đức hạnh nhờ giáo dục. Ông thích quan sát những người cha thành công (chẳng hạn vị tướng tài Pericles) nhưng không sinh ra những đứa con giỏi giang như mình. Socrates lập luận rằng sự ưu tú về đạo đức là một di sản thần thánh hơn là do sự giáo dục của cha mẹ. Niềm tin đó có thể đã có phần trong việc ông không lo lắng về tương lai các con trai của mình.

Socrates thường xuyên nói rằng tư tưởng của ông không phải là của ông mà là của các thầy ông. Ông đề cập đến một vài người có ảnh hưởng đến ông: nhà hùng biện Prodicus và nhà khoa học Anaxagoras. Người ta có thể ngạc nhiên về tuyên bố của Socrates rằng ông chịu ảnh hưởng sâu sắc của hai người phụ nữ ngoài mẹ ông. Ông nói rằng Diotima, một phù thủy và nữ tu xứ Mantinea dạy ông tất cả những gì ông biết về tình yêu, và Aspasia, tình nhân của Pericles, đã dạy ông nghệ thuật viết điếu văn. John Burnet cho rằng người thầy chính của ông là Archelaus (người chịu ảnh hưởng của Anaxagoras), nhưng tư tưởng của ông thì như Plato miêu tả. Còn Eric A. Havelock thì coi mối quan hệ của Socrates với những người theo thuyết Anaxagoras là căn cứ phân biệt giữa triết học Plato và Socrates

Nghịch lý Sokrates[sửa]

Nhiều niềm tin triết học cổ xưa cho rằng tiểu sử của Socrates đã được biểu thị như một « nghịch lý » bởi chúng có vẻ như mâu thuẫn với nhận thức thông thường. Những câu sau nằm trong số những nghịch lý được cho là của Socrates:[5]- Không ai muốn làm điều ác

- Không ai làm điều ác hay sai trái có chủ ý

- Đạo đức - tất cả mọi đạo đức - là kiến thức

- Đạo đức là đủ cho hạnh phúc

Nhận thức[sửa]

Socrates thường nói sự khôn ngoan của ông ấy rất hạn chế để có thể nhận thức được sự ngu ngốc của ông. Socrates tin rằng những việc làm sai là kết quả của sự ngu ngốc và những nguời đó thường không biết cách làm tốt hơn. Một điều mà Socrates luôn một mực cho rằng kiến thức vốn là “nghệ thuật của sự ham thích” điều mà ông liên kết tới quan niệm về “Ham thích sự thông thái”,[7]. Ông ấy không bao giờ thực sự tự nhận rằng mình khôn ngoan, dù chỉ là để hiểu cách thức mà người ham chuộng sự khôn ngoan nên làm để theo đuổi được điều đó. Điều đó gây nên tranh lụân khi mà Socrates tin rằng con người (với sự chống đối các vị thần như Apollo) có thể thật sự trở nên khôn ngoan. Mặt khác, ông cố gắng vạch ra một đường phân biệt giữa sự ngu ngốc của con người và kiến thức lý tưởng; hơn nữa, Symposium của Plato (Phát biểu của Diotima) và Republic (Ngụ ngôn về Cái hang) diễn tả một phương pháp để tiến đến sự khôn ngoan.Trong Theaetus của Plato (150a) Socrates so sánh bản thân với một người làm mối đúng đắn như là sự phân biệt với một tên ma cô. Sự phân biệt này lặp lại trong Symposium của Xenophon (3.20), khi Socrates bỡn cợt về một điều chắc chắn để có thể tạo một gia tài, nếu ông chọn để thực hành nghệ thuật ma cô. Với vai trò là một nhà truy vấn triết học, ông dẫn dắt người đối thoại tới một nhận thức sáng rõ khôn ngoan, dù cho ông không bao giờ thừa nhận mình là một thầy giáo (Apology). Theo ông thì vai trò của ông có thể hiểu đúng đắn hơn là một bà đỡ. Socrates giải thích rằng bản thân ông là một thứ lý thuyết khô khan, nhưng ông biết cách để làm cho thuyết của người khác có thể ra đời và quyết định khi nào họ xứng đáng hoặc chỉ là “trứng thiếu” [8]. Có lẽ theo một cách diễn đạt đặc biệt, ông ấy chỉ ra rằng những bà đỡ thường hiếm muộn do tuổi tác, và phụ nữ không bao giờ sinh thì không thể trở thành bà đỡ; một người phụ nữ hiếm muộn đúng nghĩa nhưng không có kinh nghiệm hay kiến thức về sinh sản và không thể tách đứa trẻ sơ sinh với những gì nên bỏ lại để đứa bé có thể chào đời. Để phán đoán được điều đó, bà đỡ cần phải có kinh nghiệm và kiến thức về việc mà bà đang làm.

Đối thoại Sokrates[sửa]

Phương pháp giảng dạy[sửa]

Các bài dạy của ông thường được chia làm hai phần dựa trên sự đối thoại:- Phần thứ nhất: Phần hỏi và trả lời cho đến khi người đối thoại nhận thức là mình sai.

- Phần thứ hai: Đây là phần lập luận: Ông giúp cho người đối thoại hiểu và tự tìm lấy câu trả lời. Ông nói: "Mẹ tôi đỡ đẻ cho sản phụ, còn tôi đỡ đẻ cho những bộ óc"

Tư tưởng[sửa]

- "Hãy tự biết lấy chính mình."

- "Con người không hề muốn hung ác tàn bạo."

- "Việc gọi là tốt khi nó có ích."

- "Đạo đức là khoa học là lối sống."

- "Hạnh phúc có được khi nó dung hòa với đạo đức."

- "Điều bị bắt buộc phải làm cũng là điều hữu ích."

Câu nói nổi tiếng[sửa]

- "Tôi biết rằng tôi không biết gì cả" (Hy Lạp cổ: ἓν οἶδα ὅτι οὐδὲν οἶδα hen oída hoti oudén oída; Latinh: scio me nihil scire hay scio me nesci

---------------------------------------------------------

Socrates

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the classical Greek philosopher. For other uses of Socrates, see Socrates (disambiguation).

Socrates

| |

| Born | c. 469 / 470 BC[1]Deme Alopece, Athens |

|---|---|

| Died | 399 BC (age approx. 71) Athens |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Classical Greek |

| Main interests | Epistemology, ethics |

| Notable ideas | Socratic method, Socratic irony |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socrates |

|---|

| "I know that I know nothing"Social gadfly · Trial of Socrates |

| Eponymous concepts |

| Socratic dialogue ·Socratic method Socratic questioning ·Socratic irony Socratic paradox · Socratic problem |

| Disciples |

| Plato · Xenophon Antisthenes · Aristippus |

| Related topics |

| Megarians · Cynicism · Cyrenaics · Platonism Stoicism · The Clouds |

Through his portrayal in Plato's dialogues, Socrates has become renowned for his contribution to the field of ethics, and it is this Platonic Socrates who lends his name to the concepts of Socratic irony and the Socratic method, or elenchus. The latter remains a commonly used tool in a wide range of discussions, and is a type of pedagogy in which a series of questions are asked not only to draw individual answers, but also to encourage fundamental insight into the issue at hand. Plato's Socrates also made important and lasting contributions to the field of epistemology, and the influence of his ideas and approach remains a strong foundation for much western philosophy that followed.

Contents

[hide]Biography

The Socratic problem

An accurate picture of the historical Socrates and his philosophical viewpoints is problematic: an issue known as the Socratic problem.As Socrates did not write philosophical texts, the knowledge of the man, his life, and his philosophy is entirely based on writings by his students and contemporaries. Foremost among them is Plato; however, works by Xenophon, Aristotle, and Aristophanes also provide important insights.[4] The difficulty of finding the “real” Socrates arises because these works are often philosophical or dramatic texts rather than straightforward histories. Aside from Thucydides (who makes no mention of Socrates or philosophers in general) and Xenophon, there are in fact no straightforward histories contemporary with Socrates that dealt with his own time and place. A corollary of this is that sources that do mention Socrates do not necessarily claim to be historically accurate, and are often partisan (those who prosecuted and convicted Socrates have left no testament). Historians therefore face the challenge of reconciling the various texts that come from these men to create an accurate and consistent account of Socrates' life and work. The result of such an effort is not necessarily realistic, merely consistent.

Plato is frequently viewed as the most informative source about Socrates' life and philosophy.[5] At the same time, however, many scholars believe that in some works Plato, being a literary artist, pushed his avowedly brightened-up version of "Socrates" far beyond anything the historical Socrates was likely to have done or said; and that Xenophon, being an historian, is a more reliable witness to the historical Socrates. It is a matter of much debate which Socrates Plato is describing at any given point—the historical figure, or Plato's fictionalization. As Martin Cohen has put it, Plato, the idealist, offers "an idol, a master figure, for philosophy. A Saint, a prophet of the 'Sun-God', a teacher condemned for his teachings as a heretic."[6]

It is also clear from other writings and historical artifacts, however, that Socrates was not simply a character, or an invention, of Plato. The testimony of Xenophon and Aristotle, alongside some of Aristophanes' work (especially The Clouds), is useful in fleshing out a perception of Socrates beyond Plato's work.

Life

Details about Socrates can be derived from three contemporary sources: the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon (both devotees of Socrates), and the plays of Aristophanes. He has been depicted by some scholars, including Eric Havelock and Walter Ong, as a champion of oral modes of communication, standing up at the dawn of writing against its haphazard diffusion.[7]Aristophanes' play The Clouds portrays Socrates as a clown who teaches his students how to bamboozle their way out of debt. Most of Aristophanes' works, however, function as parodies. Thus, it is presumed this characterization was also not literal.

Socrates' father was Sophroniscus,[8] a sculptor,[9] and his mother Phaenarete,[10] a midwife. Socrates married Xanthippe,[11] who was much younger than he and was characterized as undesirable in temperament. She bore for him three sons,[12] Lamprocles, Sophroniscus and Menexenus. His friend Crito of Alopece criticized him for abandoning his sons when he refused to try to escape before his execution.[13]

Socrates initially earned his living as a master stonecutter. According to Timon of Phlius and later sources, Socrates took over the profession of stonemasonry from his father who cut stone for the Parthenon. There was a tradition in antiquity, not credited by modern scholarship, that Socrates crafted the statues of the Three Graces, which stood near the Acropolis until the 2nd century AD.[14] Ancient texts seem to indicate that Socrates did not work at stonecutting after retiring. In Xenophon's Symposium, Socrates is reported as saying he devotes himself only to what he regards as the most important art or occupation: discussing philosophy. In The Clouds Aristophanes portrays Socrates as accepting payment for teaching and running a sophist school with Chaerephon, while in Plato's Apology and Symposium and in Xenophon's accounts, Socrates explicitly denies accepting payment for teaching. More specifically, in the Apology Socrates cites his poverty as proof he is not a teacher.

Several of Plato's dialogues refer to Socrates' military service. Socrates says he served in the Athenian army during three campaigns: at Potidaea, Amphipolis, and Delium. In the Symposium Alcibiades describes Socrates' valour in the battles of Potidaea and Delium, recounting how Socrates saved his life in the former battle (219e-221b). Socrates' exceptional service at Delium is also mentioned in the Laches by the General after whom the dialogue is named (181b). In the Apology, Socrates compares his military service to his courtroom troubles, and says anyone on the jury who thinks he ought to retreat from philosophy must also think soldiers should retreat when it seems likely that they will be killed in battle.

In 406, he was a member of the Boule, and his tribe the Antiochis held the Prytany on the day the Generals of the Battle of Arginusae, who abandoned the slain and the survivors of foundered ships to pursue the defeated Spartan navy, were discussed. Socrates was the Epistates and resisted the unconstitutional demand for a collective trial to establish the guilt of all eight Generals, proposed by Callixeinus. Eventually, Socrates refused to be cowed by threats of impeachment and imprisonment and blocked the vote until his Prytany ended the next day, whereupon the six Generals who had returned to Athens were condemned to death.

In 404, the Thirty Tyrants sought to ensure the loyalty of those opposed to them by making them complicit in their activities. Socrates and four others were ordered to bring a certain Leon of Salamis from his home for unjust execution. Socrates quietly refused, his death averted only by the overthrow of the Tyrants soon afterwards.

Trial and death

Main article: Trial of Socrates

Socrates lived during the time of the transition from the height of the Athenian hegemony to its decline with the defeat by Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian War. At a time when Athens sought to stabilize and recover from its humiliating defeat, the Athenian public may have been entertaining doubts about democracy as an efficient form of government. Socrates appears to have been a critic of democracy, and some scholars[who?] interpret his trial as an expression of political infighting.Claiming loyalty to his city, Socrates clashed with the current course of Athenian politics and society.[15] He praises Sparta, archrival to Athens, directly and indirectly in various dialogues. One of Socrates' purported offenses to the city was his position as a social and moral critic. Rather than upholding a status quo and accepting the development of what he perceived as immorality within his region, Socrates questioned the collective notion of "might makes right" that he felt was common in Greece during this period. Plato refers to Socrates as the "gadfly" of the state (as the gadfly stings the horse into action, so Socrates stung various Athenians), insofar as he irritated some people with considerations of justice and the pursuit of goodness.[16] His attempts to improve the Athenians' sense of justice may have been the cause of his execution.

According to Plato's Apology, Socrates' life as the "gadfly" of Athens began when his friend Chaerephon asked the oracle at Delphi if anyone were wiser than Socrates; the Oracle responded that no-one was wiser. Socrates believed the Oracle's response was a paradox, because he believed he possessed no wisdom whatsoever. He proceeded to test the riddle by approaching men considered wise by the people of Athens—statesmen, poets, and artisans—in order to refute the Oracle's pronouncement. Questioning them, however, Socrates concluded: while each man thought he knew a great deal and was wise, in fact they knew very little and were not wise at all. Socrates realized the Oracle was correct; while so-called wise men thought themselves wise and yet were not, he himself knew he was not wise at all, which, paradoxically, made him the wiser one since he was the only person aware of his own ignorance. Socrates' paradoxical wisdom made the prominent Athenians he publicly questioned look foolish, turning them against him and leading to accusations of wrongdoing. Socrates defended his role as a gadfly until the end: at his trial, when Socrates was asked to propose his own punishment, he suggested a wage paid by the government and free dinners for the rest of his life instead, to finance the time he spent as Athens' benefactor.[17] He was, nevertheless, found guilty of both corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens and of impiety ("not believing in the gods of the state"),[18] and subsequently sentenced to death by drinking a mixture containing poison hemlock.[19][20][21][22]

According to Xenophon's story, Socrates purposefully gave a defiant defense to the jury because "he believed he would be better off dead". Xenophon goes on to describe a defense by Socrates that explains the rigors of old age, and how Socrates would be glad to circumvent them by being sentenced to death. It is also understood that Socrates also wished to die because he "actually believed the right time had come for him to die."

Xenophon and Plato agree that Socrates had an opportunity to escape, as his followers were able to bribe the prison guards. He chose to stay for several reasons:

- He believed such a flight would indicate a fear of death, which he believed no true philosopher has.

- If he fled Athens his teaching would fare no better in another country, as he would continue questioning all he met and undoubtedly incur their displeasure.

- Having knowingly agreed to live under the city's laws, he implicitly subjected himself to the possibility of being accused of crimes by its citizens and judged guilty by its jury. To do otherwise would have caused him to break his "social contract" with the state, and so harm the state, an unprincipled act.

Socrates' death is described at the end of Plato's Phaedo. Socrates turned down Crito's pleas to attempt an escape from prison. After drinking the poison, he was instructed to walk around until his legs felt numb. After he lay down, the man who administered the poison pinched his foot; Socrates could no longer feel his legs. The numbness slowly crept up his body until it reached his heart. Shortly before his death, Socrates speaks his last words to Crito: "Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Please, don't forget to pay the debt."

Asclepius was the Greek god for curing illness, and it is likely Socrates' last words meant that death is the cure—and freedom, of the soul from the body. Additionally, in Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths, Robin Waterfield adds another interpretation of Socrates' last words. He suggests that Socrates was a voluntary scapegoat; his death was the purifying remedy for Athens’ misfortunes. In this view, the token of appreciation for Asclepius would represent a cure for Athens' ailments.[16]

Philosophy

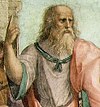

| Part of a series on |

| Plato |

|---|

Plato from The School of Athens by Raphael, 1509

|

| Allegories and metaphors |

| Related articles |

Socratic method

Main article: Socratic method

Perhaps his most important contribution to Western thought is his dialectic method of inquiry, known as the Socratic method or method of "elenchus", which he largely applied to the examination of key moral concepts such as the Good and Justice. It was first described by Plato in the Socratic Dialogues. To solve a problem, it would be broken down into a series of questions, the answers to which gradually distill the answer a person would seek. The influence of this approach is most strongly felt today in the use of the scientific method, in which hypothesis is the first stage. The development and practice of this method is one of Socrates' most enduring contributions, and is a key factor in earning his mantle as the father of political philosophy, ethics or moral philosophy, and as a figurehead of all the central themes in Western philosophy.To illustrate the use of the Socratic method; a series of questions are posed to help a person or group to determine their underlying beliefs and the extent of their knowledge. The Socratic method is a negative method of hypothesis elimination, in that better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those that lead to contradictions. It was designed to force one to examine one's own beliefs and the validity of such beliefs.

An alternative interpretation of the dialectic is that it is a method for direct perception of the Form of the Good. Philosopher Karl Popper describes the dialectic as "the art of intellectual intuition, of visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances."[23] In a similar vein, French philosopher Pierre Hadot suggests that the dialogues are a type of spiritual exercise. "Furthermore," writes Hadot, "in Plato's view, every dialectical exercise, precisely because it is an exercise of pure thought, subject to the demands of the Logos, turns the soul away from the sensible world, and allows it to convert itself towards the Good."[24]

Philosophical beliefs

The beliefs of Socrates, as distinct from those of Plato, are difficult to discern. Little in the way of concrete evidence exists to demarcate the two. The lengthy presentation of ideas given in most of the dialogues may be deformed by Plato, and some scholars think Plato so adapted the Socratic style as to make the literary character and the philosopher himself impossible to distinguish. Others argue that he did have his own theories and beliefs, but there is much controversy over what these might have been, owing to the difficulty of separating Socrates from Plato and the difficulty of interpreting even the dramatic writings concerning Socrates. Consequently, distinguishing the philosophical beliefs of Socrates from those of Plato and Xenophon is not easy and it must be remembered that what is attributed to Socrates might more closely reflect the specific concerns of these thinkers.The matter is complicated because the historical Socrates seems to have been notorious for asking questions but not answering, claiming to lack wisdom concerning the subjects about which he questioned others.[25]

If anything in general can be said about the philosophical beliefs of Socrates, it is that he was morally, intellectually, and politically at odds with many of his fellow Athenians. When he is on trial for heresy and corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, he uses his method of elenchos to demonstrate to the jurors that their moral values are wrong-headed. He tells them they are concerned with their families, careers, and political responsibilities when they ought to be worried about the "welfare of their souls". Socrates' assertion that the gods had singled him out as a divine emissary seemed to provoke irritation, if not outright ridicule. Socrates also questioned the Sophistic doctrine that arete (virtue) can be taught. He liked to observe that successful fathers (such as the prominent military general Pericles) did not produce sons of their own quality. Socrates argued that moral excellence was more a matter of divine bequest than parental nurture. This belief may have contributed to his lack of anxiety about the future of his own sons.

Socrates frequently says his ideas are not his own, but his teachers'. He mentions several influences: Prodicus the rhetor and Anaxagoras the philosopher. Perhaps surprisingly, Socrates claims to have been deeply influenced by two women besides his mother: he says that Diotima, a witch and priestess from Mantinea, taught him all he knows about eros, or love; and that Aspasia, the mistress of Pericles, taught him the art of rhetoric.[26] John Burnet argued that his principal teacher was the Anaxagorean Archelaus but his ideas were as Plato described them; Eric A. Havelock, on the other hand, considered Socrates' association with the Anaxagoreans to be evidence of Plato's philosophical separation from Socrates.

Socratic paradoxes

Many of the beliefs traditionally attributed to the historical Socrates have been characterized as "paradoxical" because they seem to conflict with common sense. The following are among the so-called Socratic Paradoxes:[27]- No one desires evil.

- No one errs or does wrong willingly or knowingly.

- Virtue—all virtue—is knowledge.

- Virtue is sufficient for happiness.

Knowledge

One of the best known sayings of Socrates is "I only know that I know nothing". The conventional interpretation of this remark is that Socrates' wisdom was limited to an awareness of his own ignorance. Socrates believed wrongdoing was a consequence of ignorance and those who did wrong knew no better. The one thing Socrates consistently claimed to have knowledge of was "the art of love", which he connected with the concept of "the love of wisdom", i.e., philosophy. He never actually claimed to be wise, only to understand the path a lover of wisdom must take in pursuing it. It is debatable whether Socrates believed humans (as opposed to gods like Apollo) could actually become wise. On the one hand, he drew a clear line between human ignorance and ideal knowledge; on the other, Plato's Symposium (Diotima's Speech) and Republic (Allegory of the Cave) describe a method for ascending to wisdom.In Plato's Theaetetus (150a), Socrates compares himself to a true matchmaker (προμνηστικός promnestikós), as distinguished from a panderer (προᾰγωγός proagogos). This distinction is echoed in Xenophon's Symposium (3.20), when Socrates jokes about his certainty of being able to make a fortune, if he chose to practice the art of pandering. For his part as a philosophical interlocutor, he leads his respondent to a clearer conception of wisdom, although he claims he is not himself a teacher (Apology). His role, he claims, is more properly to be understood as analogous to a midwife (μαῖα maia). Socrates explains that he is himself barren of theories, but knows how to bring the theories of others to birth and determine whether they are worthy or mere "wind eggs" (ἀνεμιαῖον anemiaion). Perhaps significantly, he points out that midwives are barren due to age, and women who have never given birth are unable to become midwives; they would have no experience or knowledge of birth and would be unable to separate the worthy infants from those that should be left on the hillside to be exposed. To judge this, the midwife must have experience and knowledge of what she is judging.

Virtue

Socrates believed the best way for people to live was to focus on self-development rather than the pursuit of material wealth.[citation needed] He always invited others to try to concentrate more on friendships and a sense of true community, for Socrates felt this was the best way for people to grow together as a populace.[citation needed] His actions lived up to this: in the end, Socrates accepted his death sentence when most thought he would simply leave Athens, as he felt he could not run away from or go against the will of his community; as mentioned above, his reputation for valor on the battlefield was without reproach.The idea that there are certain virtues formed a common thread in Socrates' teachings. These virtues represented the most important qualities for a person to have, foremost of which were the philosophical or intellectual virtues. Socrates stressed that "virtue was the most valuable of all possessions; the ideal life was spent in search of the Good. Truth lies beneath the shadows of existence, and it is the job of the philosopher to show the rest how little they really know."[citation needed]

Politics

It is often argued that Socrates believed "ideals belong in a world only the wise man can understand",[citation needed] making the philosopher the only type of person suitable to govern others. In Plato's dialogue the Republic, Socrates openly objected to the democracy that ran Athens during his adult life. It was not only Athenian democracy: Socrates found short of ideal any government that did not conform to his presentation of a perfect regime led by philosophers, and Athenian government was far from that. It is, however, possible that the Socrates of Plato's Republic is colored by Plato's own views. During the last years of Socrates' life, Athens was in continual flux due to political upheaval. Democracy was at last overthrown by a junta known as the Thirty Tyrants, led by Plato's relative, Critias, who had been a friend of Socrates. The Tyrants ruled for about a year before the Athenian democracy was reinstated, at which point it declared an amnesty for all recent events.Socrates' opposition to democracy is often denied, and the question is one of the biggest philosophical debates when trying to determine exactly what Socrates believed. The strongest argument of those who claim Socrates did not actually believe in the idea of philosopher kings is that the view is expressed no earlier than Plato's Republic, which is widely considered one of Plato's "Middle" dialogues and not representative of the historical Socrates' views. Furthermore, according to Plato's Apology of Socrates, an "early" dialogue, Socrates refused to pursue conventional politics; he often stated he could not look into other's matters or tell people how to live their lives when he did not yet understand how to live his own. He believed he was a philosopher engaged in the pursuit of Truth, and did not claim to know it fully. Socrates' acceptance of his death sentence, after his conviction by the Boule (Council), can also be seen to support this view. It is often claimed much of the anti-democratic leanings are from Plato, who was never able to overcome his disgust at what was done to his teacher. In any case, it is clear Socrates thought the rule of the Thirty Tyrants was also objectionable; when called before them to assist in the arrest of a fellow Athenian, Socrates refused and narrowly escaped death before the Tyrants were overthrown. He did, however, fulfill his duty to serve as Prytanis when a trial of a group of Generals who presided over a disastrous naval campaign were judged; even then he maintained an uncompromising attitude, being one of those who refused to proceed in a manner not supported by the laws, despite intense pressure.[29] Judging by his actions, he considered the rule of the Thirty Tyrants less legitimate than the Democratic Senate that sentenced him to death.

Covertness

In the Dialogues of Plato, Socrates sometimes seems to support a mystical side, discussing reincarnation and the mystery religions; however, this is generally attributed to Plato.[citation needed] Regardless, this cannot be dismissed out of hand, as we cannot be sure of the differences between the views of Plato and Socrates; in addition, there seem to be some corollaries in the works of Xenophon. In the culmination of the philosophic path as discussed in Plato's Symposium, one comes to the Sea of Beauty or to the sight of "the beautiful itself" (211C); only then can one become wise. (In the Symposium, Socrates credits his speech on the philosophic path to his teacher, the priestess Diotima, who is not even sure if Socrates is capable of reaching the highest mysteries.) In the Meno, he refers to the Eleusinian Mysteries, telling Meno he would understand Socrates' answers better if only he could stay for the initiations next week. Further confusions result from the nature of these sources, insofar as the Platonic Dialogues are arguably the work of an artist-philosopher, whose meaning does not volunteer itself to the passive reader nor again the lifelong scholar. According to Olympiodorus the Younger in his Life of Plato,[30] Plato himself "received instruction from the writers of tragedy" before taking up the study of philosophy. His works are, indeed, dialogues; Plato's choice of this, the medium of Sophocles, Euripides, and the fictions of theatre, may reflect the ever-interpretable nature of his writings, as he has been called a "dramatist of reason". What is more, the first word of nearly all Plato's works is a significant term for that respective dialogue, and is used with its many connotations in mind. Finally, the Phaedrus and the Symposium each allude to Socrates' coy delivery of philosophic truths in conversation; the Socrates of the Phaedrus goes so far as to demand such dissembling and mystery in all writing. The covertness we often find in Plato, appearing here and there couched in some enigmatic use of symbol and/or irony, may be at odds with the mysticism Plato's Socrates expounds in some other dialogues. These indirect methods may fail to satisfy some readers.Perhaps the most interesting facet of this is Socrates' reliance on what the Greeks called his "daemonic sign", an averting (ἀποτρεπτικός apotreptikos) inner voice Socrates heard only when he was about to make a mistake. It was this sign that prevented Socrates from entering into politics. In the Phaedrus, we are told Socrates considered this to be a form of "divine madness", the sort of insanity that is a gift from the gods and gives us poetry, mysticism, love, and even philosophy itself. Alternately, the sign is often taken to be what we would call "intuition"; however, Socrates' characterization of the phenomenon as "daemonic" may suggest that its origin is divine, mysterious, and independent of his own thoughts. Today, such a voice would be classified under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a command hallucination.

Satirical playwrights

He was prominently lampooned in Aristophanes' comedy The Clouds, produced when Socrates was in his mid-forties; he said at his trial (according to Plato) that the laughter of the theater was a harder task to answer than the arguments of his accusers. Søren Kierkegaard believed this play was a more accurate representation of Socrates than those of his students. In the play, Socrates is ridiculed for his dirtiness, which is associated with the Laconizing fad; also in plays by Callias, Eupolis, and Telecleides. Other comic poets who lampooned Socrates include Mnesimachus and Ameipsias. In all of these, Socrates and the Sophists were criticised for "the moral dangers inherent in contemporary thought and literature".Prose sources

Plato, Xenophon, and Aristotle are the main sources for the historical Socrates; however, Xenophon and Plato were direct disciples of Socrates, and they may idealize him; however, they wrote the only continuous descriptions of Socrates that have come down to us in their complete form. Aristotle refers frequently, but in passing, to Socrates in his writings. Almost all of Plato's works center on Socrates. However, Plato's later works appear to be more his own philosophy put into the mouth of his mentor.The Socratic dialogues

Main article: Socratic dialogue

The Socratic Dialogues are a series of dialogues written by Plato and Xenophon in the form of discussions between Socrates and other persons of his time, or as discussions between Socrates' followers over his concepts. Plato's Phaedo is an example of this latter category. Although his Apology is a monologue delivered by Socrates, it is usually grouped with the Dialogues.The Apology professes to be a record of the actual speech Socrates delivered in his own defense at the trial. In the Athenian jury system, an "apology" is composed of three parts: a speech, followed by a counter-assessment, then some final words. "Apology" is a transliteration, not a translation, of the Greek apologia, meaning "defense"; in this sense it is not apologetic according to our contemporary use of the term.

Plato generally does not place his own ideas in the mouth of a specific speaker; he lets ideas emerge via the Socratic Method, under the guidance of Socrates. Most of the dialogues present Socrates applying this method to some extent, but nowhere as completely as in the Euthyphro. In this dialogue, Socrates and Euthyphro go through several iterations of refining the answer to Socrates' question, "...What is the pious, and what the impious?"

In Plato's Dialogues, learning appears as a process of remembering. The soul, before its incarnation in the body, was in the realm of Ideas (very similar to the Platonic "Forms"). There, it saw things the way they truly are, rather than the pale shadows or copies we experience on earth. By a process of questioning, the soul can be brought to remember the ideas in their pure form, thus bringing wisdom.

Especially for Plato's writings referring to Socrates, it is not always clear which ideas brought forward by Socrates (or his friends) actually belonged to Socrates and which of these may have been new additions or elaborations by Plato – this is known as the Socratic Problem. Generally, the early works of Plato are considered to be close to the spirit of Socrates, whereas the later works – including Phaedo and Republic – are considered to be possibly products of Plato's elaborations.

Legacy

Immediate influence

Immediately, the students of Socrates set to work both on exercising their perceptions of his teachings in politics and also on developing many new philosophical schools of thought. Some of Athens' controversial and anti-democratic tyrants were contemporary or posthumous students of Socrates including Alcibiades and Critias. Critias' cousin, Plato would go on to found the Academy in 385 BC, which gained so much renown that 'Academy' became the base word for educational institutions in later European languages such as English, French, and Italian. Plato's protege, another important figure of the Classical era, Aristotle went on to tutor Alexander the Great and also to found his own school in 335 BC - the Lyceum - whose name also now means an educational institution.While Socrates was shown to demote the importance of institutional knowledge like mathematics or science in relation to the human condition in his Dialogues, Plato would emphasize it with metaphysical overtones mirroring that of Pythagoras – the former who would dominate Western thought well into the Renaissance. Aristotle himself was as much of a philosopher as he was a scientist with rudimentary work in the fields of biology and physics.

Socratic thought which challenged conventions, especially in stressing a simplistic way of living, became divorced from Plato's more detached and philosophical pursuits. This idea was inherited by one of Socrates' older students, Antisthenes, who became the originator of another philosophy in the years after Socrates' death: Cynicism. Antisthenes attacked Plato and Alcibiades over what he deemed as their betrayal of Socrates' tenets in his writings.[citation needed]

The idea of asceticism being hand in hand with an ethical life or one with piety, ignored by Plato and Aristotle and somewhat dealt with by the Cynics, formed the core of another philosophy in 281 BC – Stoicism when Zeno of Citium would discover Socrates' works and then learn from Crates, a Cynic philosopher.

Later historical effects

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (November 2011) |

Socrates' stature in Western philosophy returned in full force with the Renaissance and the Age of Reason in Europe when political theory began to resurface under those like Locke and Hobbes. Voltaire even went so far as to write a satirical play about the Trial of Socrates. There were a number of paintings about his life including Socrates Tears Alcibiades from the Embrace of Sensual Pleasure by Jean-Baptiste Regnault and The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David in the later 18th century.

To this day, the Socratic Method is still used in classroom and law school discourse to expose underlying issues in both subject and the speaker. He has been recognized with accolades ranging from frequent mentions in pop culture (such as the movie Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure and a Greek rock band) to numerous busts in academic institutions in recognition of his contribution to education.

Over the past century, numerous plays about Socrates have also focused on Socrates’ life and influence. One of the most recent has been Socrates on Trial, a play based on Aristophanes' Clouds and Plato's Apology, Crito, and Phaedo, all adapted for modern performance.

Criticism

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (November 2011) |

Socrates' death is considered iconic and his status as a martyr of philosophy overshadows most contemporary and posthumous criticism. However, Xenophon attempts to explain that Socrates purposely welcomed the hemlock due to his old age using the arguably self-destructive testimony to the jury as evidence. Direct criticism of Socrates the man almost disappears after this time, but there is a noticeable preference for Plato or Aristotle over the elements of Socratic philosophy distinct from those of his students, even into the Middle Ages.

Some modern scholarship holds that, with so much of his own thought obscured and possibly altered by Plato, it is impossible to gain a clear picture of Socrates amidst all the contradictory evidence. That both Cynicism and Stoicism, which carried heavy influence from Socratic thought, were unlike or even contrary to Platonism further illustrates this. The ambiguity and lack of reliability serves as the modern basis of criticism—that it is nearly impossible to know the real Socrates. Some controversy also exists about Socrates' attitude towards homosexuality[31] and as to whether or not he believed in the Olympian gods, was monotheistic, or held some other religious viewpoint.[32] However, it is still commonly taught and held with little exception that Socrates is the progenitor of subsequent Western philosophy, to the point that philosophers before him are referred to as pre-Socratic.